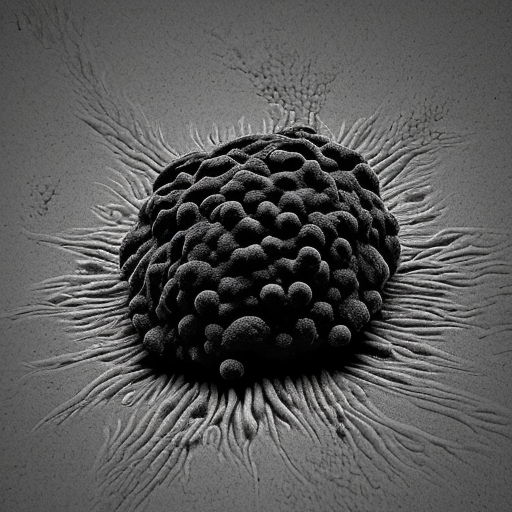

I’m going for a “clickbait” vibe with this one, is it working?

When I was getting my degree, I heard a story that seemed too creepy to be real. There was a research lab studying the physiology of white blood cells, and as such they always needed new white blood cells to do experiments on. For most lab supplies, you buy from a company. But when you’re doing this many experiments, using this many white blood cells, that kind of purchasing will quickly break the bank. This lab didn’t buy blood, it took it.

The blood drives were done willingly, of course. Each grad student was studying white blood cells in their own way, and each one needed a plethora of cells to do their experiment. Each student was very willing to donate for the cause, if only because their own research would be impossible otherwise.

And it wasn’t even like this was dangerous. The lab was connected to a hospital, the blood draws were done by trained nurses, and charts were maintained so no one gave more blood than they should. Everything was supposedly safe, sound, by the book.

But still it never seemed enough. The story I got told was that *everyone* was being asked to give blood to the lab, pretty much nonstop. Spouses/SOs of the grad students, friends from other labs, undergrads interning over the summer, visiting professors who wanted to collaborate. The first thing this lab would ask when you stepped inside was “would you like to donate some blood?”

This kind of thing quickly can become coercive even if it’s theoretically all voluntary. Are you not a “team player” if you don’t donate as much as everyone else? Are interns warned about this part of the lab “culture” when interviewing? Does the professor donate just like the students?

Still, when this was told to me it seemed too strange to be true. I was certain the storyteller was making it up, or at the very least exaggerating heavily. The feeling was exacerbated since this was told to me at a bar, and it was a “friend of a friend” story, the teller didn’t see it for themself.

But I recently heard of this same kind of thing, in a different context. My co-worker studied convalescent plasma treatments during the COVID pandemic. For those who don’t know, people who recover from a viral infection have lots of antibodies in their blood that fight off the virus. You can take samples of their blood and give those antibodies to other patients, and the antibodies will help fight the infection. Early in the pandemic, this kind of treatment was all we had. But it wasn’t very effective and my co-worker was trying to study why.

When the vaccine came out, all the lab members got the vaccine and then immediately started donating blood. After vaccination, they had plenty of anti-COVID antibodies in their blood, and they could extract all those antibodies to study them. My co-worker said that his name and a few others were attached to a published paper, in part because of their work but also in part as thanks for their generous donations of blood. He pointed to a figure in the paper and named the exact person whose antibodies were used to make it.

I was kind of shocked.

Now, this all seems like it could be a breach of ethics, but I do know that there are some surprisingly lax restrictions on doing research so long as you’re doing research on yourself. There’s a famous story of two scientists drinking water infected with a specific bacteria in order to prove that it was that bacteria which caused ulcers. This would have been illegal had they wanted to infect *other people* for science, but it was legal to infect themselves.

There’s another story of someone who tried to give themselves bone cancer for science. This person also believed that a certain bone cancer was caused by infectious organisms, and he willingly injected himself with a potentially fatal disease to prove it. Fortunately he lived (bone cancer is NOT infectious), but this is again something that was only legal because he experimented on himself.

But still, those studies were all done half a century ago. In the 21st century, experimenting with your own body seems… unusual at the very least. I know blood can be safely extracted without issue, but like I said above I worry about the incentive structure of a lab where taking students’ blood for science is “normal.” You can quickly create a toxic culture of “give us your blood,” pressuring people to do things that they may not want to do, and perhaps making them give more than they really should.

So I’m quite of two minds about the idea of “research scientists giving blood for the lab’s research projects.” All for the cause of science, yes, but is this really ethical? And how much more work would it really have been to get other people’s blood instead? I just don’t think I could work in a lab like that, I’m not good with giving blood, I get terrible headaches after most blood draws, and I wouldn’t enjoy feeling pressured to give even more.

Is there any industry besides science where near-mandatory blood donations would even happen? MAYBE healthcare? But blood draws can cause lethargy, and we don’t want the EMTs or nurses to be tired on the job. Either way, it’s all a bit creepy, innit?