Answer: it’s neoliberalism. But if that answer fills you with disgust, fear, or just confusion, please read on as I promise the explanation will be worth it.

In the wake of the 2024 election, Ezra Klein and buddies published a book called “Abundance,” and in talks and interviews they have been trying to sell it as a way forward for the defeated Democrats. The key question of the book is this: if liberal policies are so great, why do blue states have the most homelessness? Why do they have the highest overruns on their infrastructure projects? Why do they have the most difficulty building renewable energy?

These are difficult questions because they cut at the heart of the liberal/progressive promise for America. There was a half-century long political touchstone (within the American media sphere) that the Democrats were who you voted for if you cared about social issues, but you voted Republican if you cared about economics. Never mind that this misses the many socially conservative/economically re-distributive voters who saw things the opposite way, this “vote Republican for the economy” belief was one that Democrats wanted to push back on.

For my entire adult life, Democrats have been making the argument that no, “Republicans are actually bad for the economy, vote Democrat if you care about economics.” In the wake of the Financial Crisis, this message resonated, but after 4 years of inflation it seems voters no longer bought it.

Worse still, Ezra Klein’s “Abundance Agenda” argues that *you can’t blame voters for coming to this conclusion*. Blue states may be the *richest states*, but it is the Red states that are *growing*. They are building housing, they are building infrastructure, and in the next census it is predicted that Blue States (California and New York especially) will lose electoral votes to Red states (such as Florida and Texas). People are literally voting with their feet, moving from Blue states to Red states when every part of the liberal mindshare says that’s insane, and that all migration should be happening in the *other direction*. The only explanation is that people believe they’ll have higher quality of life in these Red states than what they have in the Blue states, how can that be?

Ezra Klein’s answer is that Democrats haven’t lived up to their economic promise, and they need to embrace Abundance if they are going to do so.

Much of his suggestions are things I myself have blogged about, land use should be deregulated, housing and energy should be made easier to build, and the free market should at times be deferred to to bring down prices for consumers. Government bureaucrats can’t run markets.

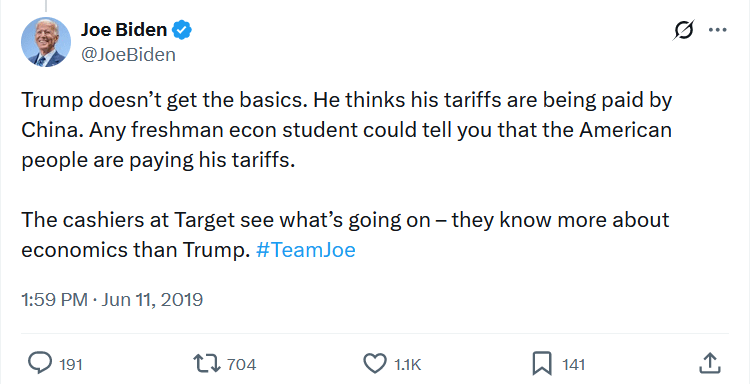

In this sense, Ezra Klein is making a (small) break with Bidenism. Tariffs on solar panels make it more expensive to build clean energy, tariffs on lumber make it more expensive to build houses.

When it’s more expensive to build things, then the supply is lower. When the supply is lower, the price is higher. If we want consumers to enjoy low prices, we should encourage higher supply by making it less expensive to build, this is the core of the Abundance Agenda. “Build what?” you ask? Everything. Housing needs houses to be built, energy needs power plants to be built, jobs need companies and factories to be built, and the Abundance Agenda encourages policies that make it cheaper to build all those things.

In essence, the Abundance Agenda is deregulation.

See, Biden is actually a pre-Carter Democrat, recall that he was elected to the Senate in 1972. The New Deal consensus at that time included a lot of skepticism of markets, and a certain degree of autarky in which the government should step in to ensure the economy is making the things it “needs” to make. So if car companies are struggling, we need to give them subsidies or protect them with tariffs, because cars are so important. Same with solar panels, microchips, and steel.

Biden’s economic record is actually reminding me a lot of Jean Jacque Servan-Schreiber, who you may remember from previous posts. Like JJSS, Biden seemed to be trying to use government power to “direct” the economy, and my criticisms of JJSS apply just as well here: governments can’t predict the future and so don’t actually know what the best investments are. Companies can’t predict either, but at least companies have price signals and the profit motive directing them towards the best bets, governments are immune from both by their sovereign nature.

JJSS wanted the Europe of the 1960s to invest heavily in supersonic planes, but we now know that those bets were quite wasteful as the fruits of their labor (Concorde) were outcompeted by the private sector (Boeing) who had already abandoned supersonic travel entirely. Will Biden’s chip foundries built in Arizona stand the test of time? Or will they be like Concorde, an unprofitable venture held up solely by the demands of national prestige, until such time as prestige becomes to expensive to maintain?

While Ezra still sees a need for government “leadership” (which I don’t, but more on that later), he is more comfortable in the post-Carter consensus, stating that governments should cut back the regulations which prevent companies from giving us cheap goods and services. Housing is expensive because governments don’t let us build houses. Energy and infrastructure are expensive because solar farms and railroads get blocked by environmental review. Even healthcare and education are burdened by over-regulation which prevents competition and protects the current megacorporations that dominate the market.

So Ezra Klein could be most accurately described as a “left-capitalist.” He is solidly on the left with regards to all social and moral issues, but does not have the skepticism of profit and corporations that Bernie and Biden do. In other words, he’s a neoliberal.

Now that is a *very* loaded term, because my time around the Internet has shown me that many people define neoliberalism as “anything I don’t like.” But philosophically neoliberalism *was* a thing, and in many ways did represent a real ideology. It was a break with the New Deal consensus on governments directing the economy, while still accepting a government role in social welfare and poverty reduction. Carter and Clinton both governed this way, and so are usually considered “neoliberals” by people who don’t consider it a slur.

Ezra Klein is therefore arguing that this “neoliberalism” should be part of the way forward for Democrats and America at large. California and New York should take more cues from Texas and Florida, at least economically. But to do so means touching a lot of third rails within the liberal coalition:

- To deregulate housing, you need to remove the ability of local residents to block new housing. This can easily be reframed as “removing local control” and “overturning democracy” if the neighborhood votes against a new house and you let it be built anyway. This deference to localism is hard to overcome politically when it’s framed in terms of gentrification and “Residents vs Corporate Developers”

- To deregulate energy and infrastructure, you need to end a lot of environmental regulations. You need to get acceptance from the coalition that sometimes we’ll have to cut down a meadow to build a solar farm, or pave over a creek to build a railroad. And if there’s a species of animal or plant that *only lives* in that meadow or creek, then you have to get buy-in that biodiversity is less important that fighting climate change.

- Energy and infrastructure also touch on “local control” and activist veto. Ezra Klein wants to make it easier for companies to get environmental lawsuits dismissed, and would likely applaud the recent supreme court decision on NEPA. But in any fight between “corporations” and “climate activists,” the coalition is inclined to side with the activists, and that will be hard to overcome

- To deregulate schools and childcare, you need to remove laws that were put there in the name of “safety.” Many states have very low caps on child-to-adult ratio in daycares, as low as 1:3, as well regulations that the workers must have a degree in childcare and training in a wide variety of emergency medical scenarios. When a certain democrat suggested raising the child-to-adult ratio to 1:4 in one city, I saw comments that “this change will kill babies,” which is a thought-terminating incitement intended to protect regulations by force of emotion, rather than reason. If 1:4 will kill babies, then isn’t 1:3 already killing babies, since we could instead be having a 1:2 ratio? Or 1:1? At some point you have to weigh up the costs and benefits, even in cases of life and death.

- And to deregulate any of these things, you need to overcome the cries that “every regulation is written in blood,” ie no deregulation should ever happen. This is yet another thought-terminating cliche but it’s one that has a lot of power on the left-side of the political spectrum.

So will Abundance succeed? Will Ezra Klein and the new “Abundance Caucus” make New York and California as affordable as Texas and Florida? Will they reverse the migration trends and made New York lose so many of its electoral votes? I don’t know, but I have more to say on this later. Now that I’ve defined what abundance is, I’d like my next post to discuss what it isn’t. Stay tuned…