This is a small addendum to yesterday’s post about forecasting.

Whenever you’re forecasting future trends, there are two general rules for the hack forecaster:

1. Every good trend will continue forever

2. Every bad trend will turn around soon

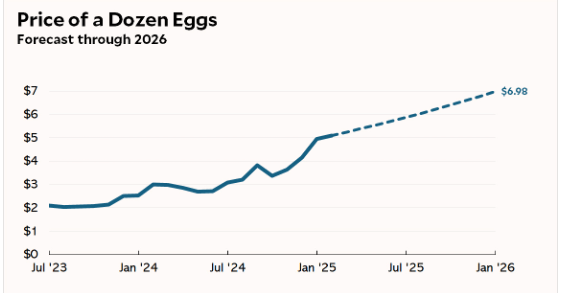

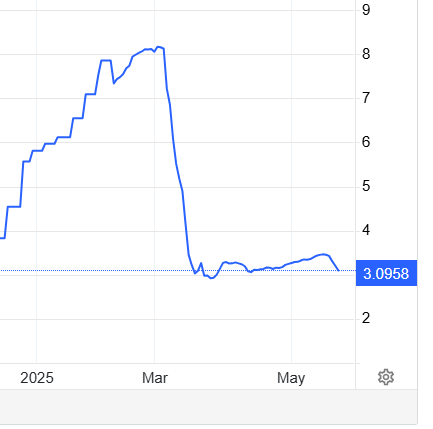

This doubly true when your forecasting has a political purpose, in which “good” and “bad” can be thought of as “supports” and “doesn’t support” your chosen narrative. A certain twitterati demonstrated this succinctly in their egg prices prediction from earlier this year:

Now I don’t want to dunk too hard on this prediction (the man died between when I first saw this and when I finally got around to posting about it), but it seems like the clearest cut case of motivated reasoning I can find. The writer was a political blogger who didn’t like the current US administration. Saddling the administration with ever-rising prices sends a strong signal that “this administration is bad for the economy.” So that was the prediction they wanted, and that was what they ran with.

Unfortunately for motivated reasoning, this is the chart of US egg prices since the start of the year.

Source, that 3.0958 just rounds to $3.10 by the way

Trends don’t usually continue monotonically forever.

Why does this matter? Well it doesn’t matter much, this is a small post. But I wanted to make clear that forecasting is easy to do when you don’t expect accountability. It’s the easiest thing in the world to draw a trendline continuing forever to support your narrative, and if you ever get pushback later for being wrong you can attack the complainers for “focusing on the past.”

I think there needs to be a lot more social accountability in forecasting. We need to stop giving a microphone to people who constantly proclaim a doom or paradise that never comes. And our society needs to be willing to hold people accountable for their predictions.

Back when 538 still existed and was run by Nate Silver, the thing that impressed me most about their predictions was the honesty with which they *scored* those predictions after-the-fact. Every election cycle they looked at every race for which they made a prediction and compared the predictions to the actual outcomes.

And surprise surprise, predictions from an actual data scientist were quite accurate. People hate on Nate Silver for predicting Trump had a 30% chance of winning in 2016 (instead of 100%, since he *did* win, or 0% since so many people claimed he could *never* win). But true to form, any event that 538 gave a 30% chance to had about a 30% chance of happening. Over the hundreds of elections that they predicted, they gave out a lot of 30% chances, and yes those 30% events did happen 30% of the time. They didn’t *always* happen, they didn’t *never* happen, they happened about 30% of the time.

That’s the kind of accountability we need, and its a shame that we lost it along with 538.