You may have thought this blog was abandoned. Nope, I’m just lazy. So I didn’t want to write about Factorio (which I have a lot of thoughts about), instead I asked my friend from the Victoria post if he’d talk to me about Victoria and I could type it and clean it up to use as a blog post. As this was from a conversation, it’s very much in stream of consciousness. But then isn’t that what this is all about?

I asked him to describe what drew him to playing Victoria 3, and he answered:

The Victoria series is a peculiar one. A mix of economics, politics, and war that this time is much heavier on the economics than anything else. The real strategy of Victoria is Soviet Planning meets Laisse-Faire capitalism: the state invests heavily into construction and heavy industry, while letting the capitalists build the consumer goods factories for the masses.

I start every game, no matter the country, by building a bunch of construction sectors. Then I build lumbar yards for wood and iron mines for iron. Construction sectors are what actually build things, they’re kind of like building companies, and the capitalists can contract them out the same as you. You get a couple to start but you want a lot more to get off the ground quickly. Wood and iron are the base construction materials at the start of the game. If you’re an industrialized nation, you can also add tool factories into the mix, as you’ll be building with tools too.

I want as much wood, iron, tools, as possible, because the larger surplus you have the cheaper it is to construct things. Building a port costs the same amount of materials no matter what, but if I can buy those for 30,000 dollars instead of 100,000, that’s a better deal. Oh yeah Victoria has a sort of supply and demand to model prices, if there’s more of a good available than what is being used, it’s price is cheaper. So when you have a surplus it’s cheap, when you have a shortage it’s expensive. A surplus of construction materials makes construction cheap.

I also want a lot of construction sectors so building goes faster. Construction can only happen at a certain rate, so even if I have infinite money and materials, I’d be waiting for years to build all the factories I wanted if I don’t have enough construction sectors.

So while I’m building out the construction economy, I’m hoping the capitalists and aristocrats of my country privatize the mines and lumbar yards I’m building. When they privatize, they give me cash and get themselves an asset in return. That asset will make money (since I’m building so much stuff), and they can reinvest that money into building more buildings later. Remember that.

But I’m spending money like water trying to build out my construction economy. I can jack up taxes but that hurts government legitimacy and makes everyone rebellious (insert American Revolution joke). And even with sky high taxes, I’ll still run a deficit while building up. So eventually my national debt will become a problem and I have to stop building before I go bankrupt. This is when I hope the rich people of my country are ready to reinvest, and give back for the good of the nation.

When rich people in Victoria own a farm or factory, they get dividends based on how profitable it is. They then use those profits to reinvest back into the economy by building more farms and more factories. Once I’ve built out the construction industry, it should be very cheap for them to start building things themselves, things like wheat farms and clothing factories. These soft goods are what my people actually want, you can’t eat iron or wear wood. So if the peasants actually want to their lives to improve, more wheat farms and clothing factories need to be built by the capitalists, which creates a food and clothing surplus letting the peasants buy things cheaper, meaning the peasants can afford to buy *more things* as well.

This is industrialization in action. The rich people who built the factories and farms reinvest their profits into building more things, like wine farms and furniture factories and eventually telephone lines. This makes all those things cheaper and now everyone can afford to live much more comfortably than when we were all living as dirt farmers. Also the rich Job Creators™ will gracious pay a wage to the factory workers and farmhands, and this wage pays better than what you can get as a subsistence farmer. So this puts extra money in my peoples’ pockets and is another way that their standard of living can increase. And since people have more money, they can demand even more stuff, which is why my capitalists have to always be building. No one is ever satisfied, we always want more, so we need to make more factories to make more goods to bring prices down, hire more people into higher and higher paying jobs so they can buy things, and reinvest all that profit we make so we can keep the cycle going. Forever.

This is economics, and it’s why I like Victoria. It takes a real stab at simulating an economy. And like a real economy, industrializing creates a virtuous cycle that spurs on more industrialization and economic expansion.

EDITOR’S NOTE: this is also why I, the editor not the talker, enjoyed Victoria 2. Vicky 2 and Vicky 3 both have their strengths, *severe* drawbacks, and plenty of edge-cases where things go crazy. But they both try in earnest to develop a real, working economics simulator that models both why industrialization was so beneficial, and why it was so hard.

Anyway, as the economy expands, it is hopefully my capitalists doing most of the building, spending their hard-earned dividends on new clothing factories and lowering the price of clothes for my people. Because as my people can afford more stuff, their Standard of Living (SOL) increases. The Vicky 3 typeface infuriatingly makes SOL look like SOI, but forget that. When the people’s SOL increases, they become more loyal to my magnanimous government that made it all happen. Should their SOL decrease, they become more rebellious (imagine that!).

So we want capitalists to build more factories so people can afford more goods so their SOL increases so my regime becomes stronger and more resilient to all the violent revolutionaries/liberals who would overthrow my absolute monarchy.

See Chapel Comics to understand the joke about liberals https://www.chapelcomic.com/64/

Now I made it sound complicated-yet-manageable up there, but trust me like any good economic simulation there are a ton of moving parts. In addition to micromanaging what your country builds, you can micromanage its trade, setting up each and every trade route with foreign nations. It’s *kind* of OK. Trade routes cost convoys (which you build at ports) and bureaucracy (which you build at government institutions). So there is still the Victoria 2 problem of there being no travel cost for goods, (a sheaf of wheat costs the same whether you bought it from the next town over or from China). But by having trade require limited resources the player is at least fenced as to how much trade they can easily do.

And while the game does sort of try to model different economic systems, you’re still playing God even in the Laisse-Faire capitalistic system, you’re still an all-knowing god building the construction sectors and various heavy industry.

So that’s the stuff I like about Victoria 3, so why couldn’t I convince my friend to play it?

EDITOR’S NOTE: really I didn’t want to buy another paradox game and sign up to a lifetime of DLC

Well I love Victoria 3 as an industrialization simulator, but it doesn’t do much besides that.

So let’s say you’ve built all the heavy industry and now construction is cheap in your country. Let’s say you keep on top of things as your economy grows, expanding the construction sector to meet new demands, upgrading your factories with newer technology, and so on. What else can you do once you have a strong, powerful empire?

Not much really.

In fact, upgrading your factories is sort of a frustrating minigame in and of itself. In older games, researching a new technology would just apply a flat boost to all your factories that used it, researching a better plow made your farms better. Now however, you have to actually tell all your farms to use that newer and better tech, and that tech will have some cost (of iron, or tools say) that your farms will have to pay in order to use it. If you upgrade your farms without having enough iron or tools for them to use, you can actually cause them to lose money as the grain they sell doesn’t cover the cost of the tools they use.

But why am I an omniscient god telling everyone how to run their farms? Who cares.

OK not sidetracked now: what can you do besides economy?

Well war sucks, so don’t do that. I mean in the game by the way, it is never fun in real life but games should be fun and in this game war isn’t. They decided moving every individual army was boring an unrealistic, so instead you vaguely tell all your units to go fight along a “front” and they’re supposed to do all the action for you. A few problems with this:

First, a “front,” is very very vague and yet each army can only and exactly cover one front. The whole border between Russia and China could be a front. Or two neighboring towns in Germany could be two different fronts. It all depends on how the AI decides to split up the map and sometimes it chooses poorly. But regardless of how the fronts are split up, a single 60 division army can cover exactly one front, and it will always be able to reach every battle along a ridiculously long front, but will never be able to fight a battle happening on a different front even if it’s within spitting distance.

But then, how exactly do the armies even fight on these fronts? It’s pure diceroll and I don’t know if any skill is involved. I click to tell my armies to go to a frontline and fight the enemy, then war vaguely happens offscreen, and I can neither influence it nor does it influence me.

See, wars in Vicky 3 are strangely bloodless affairs. Soldiers are supposedly dying, territory is blasted with artillery, but it doesn’t seem to affect anything besides a vague “war weariness” number that ticks up until you’re forced to surrender or you win. If your territory is conquered, you still get all the money from it, your people are still working their jobs, and all the factories are still sending ammo and artillery to your frontline (even though the factories themselves are behind enemy lines). If your army is annihilated, they flee back to your territory to rest and recuperate, but you never see units wiped out that you have to replace, or see the effects of all the dead soldiers on your populace. It’s weird, bloodless is the only way I can really describe it. It’s like they *had* to have wars, because you can’t simulate the 19th century without them, but they didn’t want war to interrupt the economics lesson so they just put it to the side.

EDITOR’S note (long one this time): This is a complete change to how war was in Victoria 2. Not only on a higher level, in that Vicky2 let you move around every individual division, but on a lower level in how war effected the rest of the game.

Occupied provinces in Vicky2 didn’t send you taxes or resources. Their factories were blasted to rubble, their farms were torn to pieces. The people living there would slowly run out of supplies, which not only lowered their life expectancy but made them militant and angry, angry enough to start a revolution. More than once I would be fighting a war only to see enemy rebels pop up in the lands I had occupied, the occupied people deciding now was the time for a revolution to overthrow both invaders and oppressors. Wars could turn into an interesting 3-way dance in this way, or even a 4-way dance if multiple different groups rebelled simultaneously.

And beyond the front lines, the soldier pops themselves were important. Soldiers staffed their regiments, and as they died in battle new soldiers needed to replace them. That meant that during war you’d have to use your national focus points to encourage other people to become soldiers and fill the ranks, essentially you put on a huge recruiting drive, and that took away from your abilities to raise literacy or factory output or anything else. The soldiers themselves all had an identity too, and a home they were from.

There might be a regiment of say Hungarian soldiers in Vienna. They might have come from Hungarian people migrating to the Big City for work, and then being encouraged to become soldiers and join the army by your recruitment drive. You can form them into a division, and as they take loses those Hungarian soldiers in Vienna will shrink more and more and more. Eventually their division will take so many loses that it will completely disappear, along with the soldiers it was connected to.

There may be other Hungarians, other Viennese divisions, but the *Hungarian Soldiers From Vienna* could come to an end, all because of a single bloody war where their division took the brunt of the fighting.

You could see these effects happening in real time. If you recruited soldiers mostly from your nations ethnic minorities, then they’d be the ones to take most of the loses in your wars. And if your nation discriminated against ethnic minorities, you could find that your own soldiers would rise up and join the rebels when the time came.

None of this seems to happen in Victoria 3 wars. Farms, factories, and soldiers aren’t all that troubled by the killing, dying, and destruction. It’s one of the biggest misses in a game full of misses, war doesn’t seem like war.

But unfortunately war is the major way you can interact with an affect the game world. The AI knows it too, and can be a lot more trigger happy in this game than previous one. Victoria 2 had a habit of AIs being fairly passive unless you screwed with them. The “crisis” system was supposed to satisfy a player’s warlust by forcing all the great powers to have a showdown every decade or so, but if you weren’t in Europe you could ignore the crises and everyone else would ignore you (mostly).

Now though a strong AI is happy to march their army to war anywhere, anytime, for any reason. Russia will send everything it has to Spain in order to support the independence of the Phillipines. Britain will march on America because they want to change the rulership of Liberia (America’s protectorate). Italy will send everything it has to Guatemala just because they didn’t want to join Italy’s alliance. These are all wars that are possible, but somewhat fantastical because in the real world nations didn’t send large armies halfway across the world just for kicks. Wars happen either with large armies close to home or with very small armies very far away, you don’t send out everything you have because what if your neighbors want to try something while your whole army is away? You could be conquered in a day by someone far smaller than you.

EDITOR’S NOTE: fun fact, this was kind of the case in WW1. I was watching a show that pointed out that Germany delayed the implementation of unrestricted warfare submarine warfare until it could bring units back from the Eastern front to station on the border with Denmark. Submarine warfare didn’t just piss off the Americans and bring them into the war, it pissed off all Germany’s neighbors and could have brought any one of them into war. There was a real fear that with literally the entire army in France and Russia, a nation as small as Denmark could pull a surprise invasion and be in Berlin before anyone could react, and they would definitely have a reason to if German subs started sinking a lot of Danish ships

So war feels very very gamey, AIs are way too willing to throw down for the slightest cause, but then again war is so painless that they might as well do so yeah?

On and politics? It’s ok I guess. Very confusing, very deep, very much something that you dream about and think “oh I wonder what cool things I can do!” Then you actually play the politics and it’s not much.

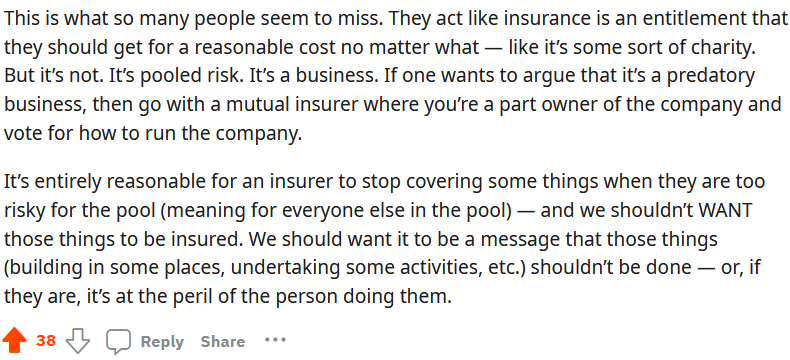

It’s not the worst when it interacts with economics I’ll say that much. See the powerful people in your country are split up into interest groups (IGs) that have their own ideals and their own desires. And in a non-industrialized nation, most of the power is held by the large landowning families. And surprise surprise they don’t like changing the laws in any way that would negatively affect them. So maybe you want to rationalize the economy to allow for private investment, open up trade to allow for importing of valuable goods, or ending serfdom to allow peasants to take factory jobs. Any one of those is a threat to their power, so the landowners will forbid it. And if you try to force the issue, they’ll rise in rebellion and overthrow you, reverting all your hard-fought laws to back to how they were before your reforms.

Reforming an economy in the politic sense is thus an uneasy balance of placating the powerful landowners, undermining their influence where possible, and desperately trying to enact laws before they can rise up against you.

But once you’re past that, the politics is just timers and dicerolls. There really isn’t much you can do to direct the fate or your nation. You can sometimes invite foreign agitators to try to start a movement for some cause or another. You can suppress or support some interest groups to get them to be powerful enough to pass laws. But it is really all down to chance and factors outside your control. And there isn’t any real novelty to the politics either, there is pretty much always a “best” law that you want to be aiming for at any one time. So no matter your nation no matter your starting position, you’ll be trying to pass the same laws the same way everywhere using the same dicerolls and timers.

Not exactly fun.

I’ll end on a final note about Power Blocs, or rather what they should be called which is the EU-lite. Power Blocs aren’t what they seemed to be named after, where multiple countries join together for a common cause. Instead they’re modelled almost exclusively after the British and Russian empires, where one nation (Britain, Russia) is *really* in charge but let’s other nations (Canada, Finland) have a tiny bit of sovereignty as a treat. Those nations can set some of their own policies, but their ultimate fate is to either be swallowed up and annexed by their overlord, or fight a war and escape. Or I guess wait for their overlord to fight a big war and then ask to leave, that works too.

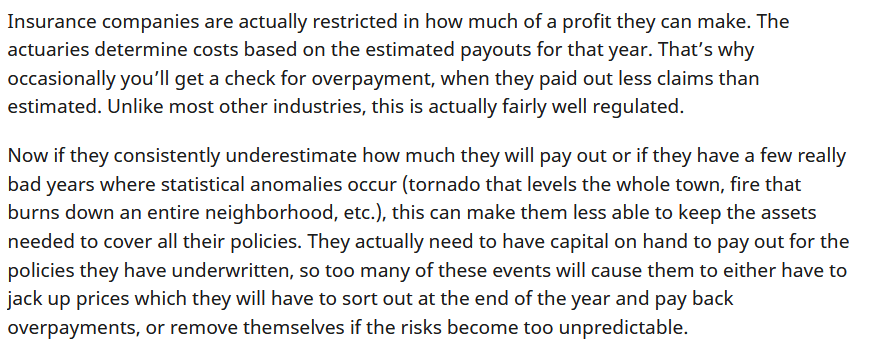

Anyway why would anyone join a power bloc, when it all leads to annexation? Well the key is the EU part of it. Nations in a power bloc all share a single market. You should read an economist for a good deep dive as to how common markets are more efficient, but the game does do a damn good job at modeling that too. You the player don’t have to make sure your own nation produces one of everything, instead other nations can produce some stuff and sell to you in exchange for your stuff. This lets everyone specialize in their comparative advantage, and unlike the normal trade system this doesn’t cost bureaucracy or convoys, the trade is automatic.

What this means is that as soon as Britain start building factories to make tools, the rest of its Empire benefits from lower priced tools. Britain also benefits from having a captive market for its finished goods, sure it’s a lot harder to overproduce tools and cause a surplus that makes your construction cheaper, but you can also let your factories go wild on producing the most high value finished products, because you’ve always got a captive market to sell to. In turn you can buy up their low value products to keep your population satisfied and keep their standard of living (SOL) rising.

It all makes a certain kind of sense. I formed a power bloc as America that was a kind of Trade League, which seems to be the only type of Power Bloc that doesn’t end in Annexation. I invited all of Central and South America into my EU-style trade league, and my population’s SOL shot through the roof. Overproduction of a good isn’t always useful, because if the cost goes down too much then the people working in the factory don’t get paid (because there is no profit). This can end with a depression cycle, where their income goes down so their SOL goes down so they buy less meaning the factories sell less meaning their income goes down more, etc. But all of the Americas was my captive market, any time I build a factory there was someone somewhere to buy the surplus.

And since I had all the best tech, it was always better for the factories to be built in America rather than anywhere else, so it was always my people who got the high paying factory jobs. The rest of the Americas usually only worked the jobs that were cut off by geography instead of economics. Large scale coffee and rubber farming for instance. My capitalists opened rubber farms anywhere they could in South America, and since my factories needed the rubber those rubber farms paid a lot better than any of the less efficient factories opening in those South American countries.

This created a sort of anti-capitalist’s nightmare, capitalism was working by way of a permanent underclass. The workers in America were getting ever richer because they were producing finished goods to export to South America. The workers in South America couldn’t compete with the American factories because their nations didn’t have the tech that America did. They were instead relegated to rubber, coffee, and any other jobs that just couldn’t be done in America or couldn’t be done efficiently. But they were still benefiting from a rising standard of living (SOL) because the cost of rubber/coffee/etc was rising thanks to American factories and American demand for goods. This lead to South America also having a rising SOL, just one that was never as high as America, and was capped well below America’s.

The one problem is that that isn’t how it really works in real economics.

The technology of a factory isn’t determine by what country it’s built in, but by the technology available to the investor. When Apple started building factories in China, they didn’t use Chinese technology (which at the time was well behind America’s). They brought over all the innovations and insights from Silicon Valley and set up all the tech there. The factories of China used all the same high tech you’d find anywhere else, just with a lower cost of labor.

That should be the case in Victoria 3 as well. It doesn’t make sense that South American factories can never keep up with American ones, if an American capitalist built both then the assembly lines, automatic sewing machines and so on can be brought and shipped to a factory whether it’s in Columbus or Colombia. You’d expect outsourcing to happen in this scenario, same as happened with China in the 90s and 2000s, but since the technology of a factory is determined by where it’s built and not who builds it, we instead get the anti-capitalist’s nightmare described above.

One final fun fact to end this one: Hawaii was also in my Power Bloc. I checked the rankings at one point and it was the damnest thing: Hawaii’s standard of living (SOL) was head and shoulders above anywhere else on earth, even my own SOL in America.

Most nations start the game at SOL of 9 or so. Industrialized may start at 10, lower tech nations may start at 8. It’s long and hard to improve your SOL but I’d done a respectable job of bringing America’s SOL up to a baseline of about 20, double what it was at the start and bringing my nation from its starting point of “impoverished,” up through “middling” and into the giddy heights of “secure.”

Hawaii by contrast had an SOL of *35*, way past “secure” and “prosperous,” all the way to “affluent.” I was shocked, how had this happened?

Well the EU is how, and in a funny way. See since all the best paying jobs were in America, the people migrated to where the jobs were. America starts the game with roughly open borders, and if you keep it that way the tired, poor, and huddled masses will be very happy to leave their rubber/coffee jobs and come live in America to work in car factories and get paid 3x as much.

Hawaii starts the game with a miniscule population, and it seemed almost every dang one of them had left and gone to America. So who was even left to live it large in Hawaii with the SOL of 35? The capitalists, of course.

Capitalists can invest in factories remember, and at some point the Hawaiian capitalists had taken advantage of my EU power block to invest in an American factory. Naturally it was doing gangbusters, and they in turn were swimming in dividends. So of course they could live the high life, buying lots of stuff since my factories had made everything so cheap. They could have lots of clothes, porcelain, furniture, even a car or two. And since all the working classes had gone off to be Americans, the wealthy capitalists were the only ones left on the islands. This defaulted Hawaii’s SOL to the SOL of the poorest capitalists, an affluent 35 or so.

But wait, if all the working classes left, who sold the capitalists their food? Who brought over the cars from America, who built their homes and fixed them after the storm?

No one, like a lot of things Victoria 3 abstracts that all away. If goods aren’t moved by rail they move by magic, so everything can come off the factory floor in America and teleport magically to the rich capitalist in Hawaii, who never needs to hire a poor handyman to fix his windows or garage either.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Anyway that’s Vicky 3 in a very long nutshell. As my friend describes it, you’re here for the economy and *nothing else*. If economics doesn’t interest you, I hope you don’t mind my blogging. But if it does, I hope war doesn’t interest you because Vicky 3 doesn’t do it well. I’d like to say this will be the last time I make a post this scattered and unusual, I wanted to write but didn’t want to so I had someone else write for me essentially. Hopefully next week we’ll be back to Factorio, I swear I still have much to say about it.