-

Are stocks-as-memes creating market inefficiencies?

Stocks have long been the investment vehicle of choice for people with small amounts of excess cash. Bonds are confusing, bank interest doesn’t pay much, and property requires high amounts of cash that most people don’t have. But stocks are easy to understand, potentially give jackpots, and require such a small amount of upfront investment that almost anyone can afford them. In ages past stocks were still usually bought through a specialized broker, and while the shoe shine boys in New York giving out stock tips may have been seen as a signal of a price crash, most people not living in major cities didn’t have access to a broker who could help them buy. The brokers were therefore a barrier to entry that prohibited a lot of people from owning stocks who otherwise might have. These days buying a stock can be as easy as installing the app, so quite literally anyone can own one at the push of a button. This has democratized the market, but may have led to some unexpected consequences.

It seems that these days, stocks have become more than an investment opportunity. Some stocks can be a badge of honor, a feeling of belonging, or a source of self-actualization. You may invest in nuclear power because you want to help fight climate change, you may invest in Manchester United because you love the club, you may invest in GameStop because you believe you’re destroying the short sellers and want to be part of something greater. None of these feelings have anything to do with the stock’s financial value. They aren’t a dividend, they aren’t growth, they are a feeling you have when you own the stock and those feelings are often irrational. In some ways these feelings call into question our understanding of stocks and investors generally.

Now let’s be clear, there has always been emotions in the stock market. Some people have always bought a company simply because they “liked” it with no better reason why, and “panics” can be just that: mindless rushes to cash out based on fear without thought. But when a stock’s price is almost entirely based on feeling rather than actual value, to some extend it forces us to re-evaluate the market as a whole. Last year, GameStop’s stock rose exponentially for no good reason whatsoever, and while some have considered it nothing more than a bubble, the price remains irrationally elevated even today. There is no way a stock with no growth, no earnings, and no path to profit should be trading so high, and yet it is. If you took a company that was identical to GameStop in every way, but called it something different, it would have but a small fraction of GameStop’s market cap. That’s because GameStop isn’t just a company, GameStop truly is a meme. It seems insane, but there truly is a group of people for whom ownership of GME stock is bringing them no financial value whatsoever, but who continue to hold it out of emotional value. You wouldn’t think such a group would be big enough to move the market, but last year showed them to be plenty large, and I believe there are still enough of them hanging around, holding the stock, and even buying more to ensure continued upward pressure on the stock’s price.

If a market is anything, it is a mechanism of price discovery. The stock market should be a mechanism to discover the correct price of companies, and our research assumes that this in turn allows profitable and growing companies to prosper while unprofitable and shrinking companies fail. We know market actors can be irrational, but the average of all market actors, the “wisdom of the crowds” so to speak should have some logical underpinning if the market is to find the correct price of these companies. Stocks becoming a form of self-expression more than an investment vehicle could introduce inefficiencies to this market, and I’ll still trying to come to grips with what the consequences could be. We might imagine a future in which board members will seek out a CEO based not on the value they can add to the company but by whether or not they, like Ryan Cohen, have a ready-made base of support among the memesters. But I don’t have the economic or statistical background to understand how much this would change things, maybe CEO’s have always been picked for dumb reasons. What do you think?

-

Gas is expensive, isn’t that a good thing?

So this post will be a little political, but laying all my cards on the table: global warming is happening and does need to be fixed. Decarbonization and renewables is a laudable goal that our country and world should be working towards. With that said, why are the environmental champions bemoaning the consequences of their own actions? For a long time, Democrats have been reminding us that raising the price of gas is the quickest way to make people use less of it. And this is absolutely true, as price goes up, demand goes down. In addition to direct carbon taxes, Democrats were proud to campaign on reducing domestic fracking and the production of oil and pipelines for the entirety of the Trump presidency. But now it feels like an “oh no, the consequences of my own actions” moment as the price of gas rises and Democratic administrations struggle to lower the price at the pump. The Strategic Oil Reserve has been emptying in order to reduce prices, many Democratic controlled states have suspended their gas taxes, some states are directly compensating drivers. All these things subsidize the price of gas and therefore increase it’s usage. Which is absolutely contrary to every effort and piece of climate messaging we’ve seen for the past 5 years at least.

I just feel like this should have been obvious, if domestic oil production goes down, then the price of gas will go up. We should have known that people wouldn’t like the price of gas going up, and someone should have thought about “how do we mitigate the harm to consumers if the price of gas goes up?” But instead that question was ignored, and now since the price of gas has gone up due to things outside the Democrats’ control (OPEC, Russia), the only response is to desperately try to bring the cost back down again. It makes a nonsense of all the efforts that came before it. There are ways to mitigate the harm to consumers brought about by the price of gas, but it should have been obvious that this would be the result of pro-climate policies.

-

Halloween feels bigger than Thanksgiving now

Yard decorations, parties, whole store aisles dedicated to it, I don’t think we’ll have quite so much of that for Thanksgiving this year as we’ve had for Halloween. Halloween has always been a bit of an American tradition, but it feels like it’s exploded in popularity during my adulthood to the point that Halloween parties have now been added to the list of corporate/academic events that serious employees will attend to have a bit of drink and fun and goof off with their bosses and coworkers. What used to be a party mostly for children and collegiates has come into its adulthood and is now a part of the American rolladex of holidays.

I’m not at all sure where this began or when, but I’m wondering if it’s somewhat inevitable for all holidays to expand if the culture allows them. People like goofing off, and having more excuses to do so by turning Halloween into a “season” instead of just a single night of kids asking for candy is something that people will enjoy. I only wonder if Thanksgiving will follow this trend and we’ll have an entire party season from September through January in some distant future.

-

In science, be willing to say something’s wrong

This is a short one today, it’s been a busy week. I just wanted to share an anecdote from my work:

We’ve been operating under a certain hypothesis for as long as I’ve worked here. We think if we do a certain experiment a certain way we’ll get certain results. We haven’t managed to get those results yet but we are tweeking and revising the experiments in an attempt to do so. Yesterday I randomly ran into a professor who shared with me a paper he had just published, a paper which seemed to indicate that the results we were searching for my not be possible, or at least might not be possible using the experiment we were doing. Now why had we believed our experiment would work? Well we read a different paper that seemed to indicate it would.

So now I have a conundrum, I have this old paper that says what we’re doing will definitely work, and this new paper saying maybe it won’t. What do I do? I start by re-reading both papers to make sure I’m not misunderstanding them, and I come upon something I never realized: the old paper may not have proven what it thought it proved. Maybe the results from the old paper are actually closer to the results from the new paper, but were just interpreted wrong. If that’s the case then the new paper is correct and our experiment won’t work. We read the old paper and believed it’s interpretation, but we didn’t put enough effort into validating that it’s interpretation was correct based on its data, we assumed the paper had done that well enough. But with the benefit of the new paper we can see that maybe its interpretation was wrong.

This is a very heavy conclusion: the paper we have been basing our research on might have a wrong conclusion. It’s a harsh accusation but in science it’s sometimes necessary to speak out and make these accusations. You can’t keep going down the wrong path or you’ll never go anywhere.

-

Markets tend towards completeness: the story of Ric Flair and terrorism

There’s a funny story about Ric Flair: Flair was at the height of his career making millions of dollars every year, but he knew that the good times would someday end and that he had to invest his money for retirement. He decided that he would invest in a business he knew well, and what could be a better business than a gym. Wrestling is a body business, and during his world travels as a wrestler Flair had been to all sorts of gyms to keep his physique in top shape for his matches. He knew what he liked and knew what a gym needed, so he put his money into building a high-end luxury gym in the Bahamas, then he starting dropping the name of his new gym in his promos so his legions of fans would want to buy memberships there. It was all coming together, but tragedy struck when in its very first year of operation a hurricane hit the Bahamas and wiped out Flair’s gym. Flair was distraught, but his friend tried to comfort him saying “surely you haven’t lost everything, didn’t you have insurance?” Flair shot back “what do I look like, an idiot! Why would I ever pay for insurance!”

It’s a story I like because it speaks to the mindset of many professionals, most of whom can be experts in their own field but just don’t understand how finances work. It’s easy to throw your hands up and see financial markets as a tool by evil rich people to take our money, but it’s important to know that everything in finances is just a bet or a hedge usually made in good faith. When you insure your property, you’re reducing your downside risk by ensuring you get a payout if the property gets destroyed, but in turn you reduce your upside return because you’re forced to pay for the insurance for as long as you hold the policy. The insurance company meanwhile is increasing their downside risk because they have to pay you money if your property gets destroyed, but in turn they increase their upside return by forcing you to pay them money for the policy. The insurance policy can also be seen as a kind of bet: the person paying for insurance is betting that the value of the payout will be more than the amount they pay towards the policy, aka a hurricane is more likely to hit the property. The issuer of the insurance is betting the opposite, that the payout will be less than the amount paid towards insurance. It’s funny to realize, but buying hurricane insurance is sort of like a placing bet that your property will get hit by a hurricane.

But what if the insurance company wants to reduce its own risk? There are various tools and instruments an insurance company can use to hedge its risk, in the same way a gym owner can use insurance to hedge the risk to a gym, and they all work in much the same way: one party bets than an action will happen, one party bets that it won’t, and the money goes to whoever is correct. A whole bunch of insurance policies can be securitized into catastrophe bonds for example. Let’s say Ric Flair builds a second gym and this time he insures it, in that case the insurance company can sell catastrophe bonds based on his policy. Now let’s say I buy 100$ worth of catastrophe bonds based on Flair’s insurance policy: the bond has a lifetime of 3 years, so if after 3 years no hurricane has destroyed Flair’s gym then I am entitled to my 100$ back plus some extra money known as the “coupon.” If on the other hand a hurricane does destroy Flair’s gym, then I lose my 100$ investment because the insurance company takes it to pay back Ric Flair. By buying this catastrophe bond, I am participating in a bet in which I think a hurricane won’t destroy Flair’s gym, and I make money if my bet is correct.

Now remember that a catastrophe bond is a security, it’s like any other bond that I can sell on the open market. If I need money, I can sell my bond to someone else for a fair value, but the amount I can sell it for will change as it gains or loses value based on outside forces. Say for example that scientists publish a report saying that the upcoming hurricane season will be the most destructive in history, suddenly it looks more likely that Ric Flair’s gym will get destroyed, meaning my bond won’t pay back the money, meaning the price of my bond will go down because people think it’s a less good investment. The opposite could occur too, if the Bahamas institute some national policy which mitigates hurricane risks for all residents, then it becomes less likely that Flair’s gym will be destroyed and thus more likely that my bond will pay back the money, so the price of my bond will go up. And because the price of bonds can go up or down, you can go short or long on them essentially betting on their price movement which is in part determined by the underlying risk.

Now let’s add another twist: hurricanes aren’t the only thing you can insure against, what about terrorism?

Let’s paint a scenario in which Ric Flair insures his gym against terrorism instead of hurricanes. The insurance company securitizes his policy into a bond which someone buys, I then take a short position against that bond. My short position means I’m betting the price of the bond will go down, and why would it go down? It could go down in part because people think terrorism is more likely to happen and destroy Flair’s gym, and in the aftermath of large terrorism attacks many catastrophe bonds’ prices do go down as the markets become fearful of follow-up or copycat attacks. By shorting a catastrophe bond on Ric Flair’s terrorism insurance, I make money whenever terrorism happens.

This exact situation has been seen by some as a monstrous moral hazard because since I get paid when terrorism happens I have a financial incentive to support policies that make terrorism more likely. What those policies are I won’t speculate, but some have painted grim pictures in which hedge funds could secretly move money to support terrorists in order to scare the market and make bank on their investments. In the aftermath of the Financial Crash this even led some to propose banning securitized insurance altogether, because not only was it speculative and dangerous just like the credit-default-swaps that were blamed for the crisis, but it also came with an in-built hazard in that people were incentivized to ensure terrible events happened. I feel like this is a misunderstanding of financial markets: these markets tend towards completeness. What that means is that every angle of a financial transaction tends to have space for someone to make a bet, because if there’s no monetary incentive for the price to move in every possible way then there’s less of a mechanism for price discovery. If you can securitize a loan then you can securitize an insurance policy, and if you can short a stock you can short a bond, these are just ways for companies to hedge their risk and for the market to discover the correct price of something. And note that the person shorting a catastrophe bond isn’t the only one with a financial incentive for terrorism: Ric Flair himself would have a financial incentive since he gets an insurance payout if his gym gets destroyed by terrorism. We’ve had laws to investigate and prevent this kind of thing for hundreds of years with arson and other forms of insurance and if we think people are breaking those laws then we should investigate and prosecute them, not ban an entire financial market.

-

Remember when Monkeypox was the next COVID?

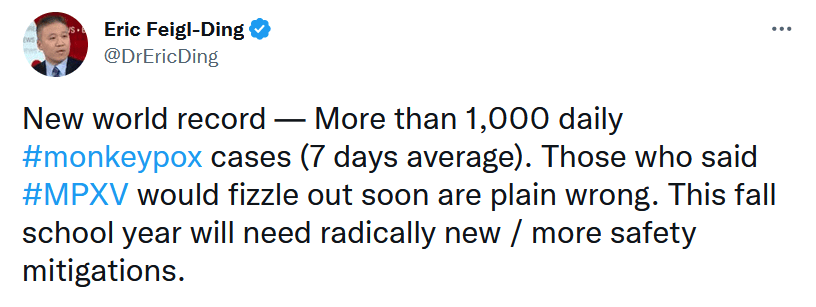

Oh the halcyon days of three months ago. I was younger, the air was warmer, and twitter was aflutter with hysterical reports on how Monkeypox was rampaging through the population and would soon run wild through schools as soon as the fall semester began

Tweet from August 2nd 2022 Today Monkeypox is in the rear-view mirror. The vaccine rollout was stymied by some impressively bad government bureaucracy, but the vaccines worked, the virus was only as contagious as the experts said, and spread almost solely through the populations the experts said it would. It was never airborne, and it never ran rampant the way doomers thought (hoped) it would.

Speaking of the distant past, remember Credit Suisse?

Absolutely no hint of irony A few weeks ago, Credit Suisse was supposed to have a “Lehman Brother’s” moment, their debt was so extraordinary that they were destined to collapse, taking the global banking system down with them. There’s up 20% in the last month and show no signs of default.

Remember Shanna Swan? She’s made headlines claiming that the human race could go extinct due to chemicals in our environment destroying male fertility. Personally I knew this claim was bunk from the moment I read it because biologically speaking, human reproduction is basically identical to all mammalian reproduction. If human fertility really was plummeting due to the chemicals in our environment, then other mammals (the cows we ranch, the dogs and cats we live with, even the rats that infest our subways) should have also seen plummeting male fertility due to their bad luck of sharing the planet with us. Yet somehow no overall drop in mammalian fertility was recorded, this catastrophe only affected humans. No ranchers complained of an inability to fertilize their cows, no reduction in stray dogs and cats was reported due to drop in male fertility, this was somehow the one biological process that humans and no other mammals were subject to. It turns out there was a good reason for that because her whole doom prediction was junk and rested entirely on flawed assumptions.

I’ve grown pretty tired of the endless predictions of collapse doled out by social media. Every week it seems there’s another new thing that will destroy us all but when life carries as normal none of the prediction-mongrels ever admit they were wrong. There’s more than enough actual bad things out there without social media taking misunderstood factoids and extrapolating the complete worst-case scenario out of it all. I’d like to have some more accountability for prediction-mongers but social media makes that impossible as by the time some coming catastrophe can be conclusively proven false, a new one has been conjured up in its stead. Repeat ad nauseam, giving constant predictions of collapse and using any downturn of any kind as evidence for your accuracy. It’s just tiring.

-

“No one wants to work”

Inflation is up, unemployment is down. This year there have been tons of stories about shortages and supply chains, and invariably a call has arisen from business owners: they’d like to hire more people but no one wants to work.

When I see stories on local restaurants and businesses closing, inevitably I see an owner blaming their failures on no one wanting to work. They had a good and profitable business going on, then after the pandemic suddenly no one wanted to work anymore. This meant they couldn’t hire employees and so couldn’t do anything at all to make money and thus were forced to close down. This is a dumb argument for many reason’s but to just pick one: labor has a market just like any other service. There is a supply and a demand for labor. If you are demanding labor while the supply is constricted, the price you pay for labor will go up, and if you refuse to pay that price then you will go without, just as if I refuse to pay more for a Pepsi I can’t get one. The price you pay for labor is the wage or salary so if you can’t get people to work for you then you need to increase the wage or salary you are offering. No one is going to work for less than the market rate and so if you can’t afford the market rate of labor then I’m sorry but you’re going to go out of business just as if you couldn’t afford the market rate of rent or supplies or anything else a business needs. People want to work, but no one wants to work for you if you’re not willing to pay them.

This “no one wants to work” nonsense got spread around a lot as the price of labor increased and many businesses found themselves unprofitable. It was easier for owners to blame the moral failing of society than to admit that they weren’t good enough to turn a profit in a high wage environment. But while this nonsense was rightly criticized by many, it reminded me of a similar economic trope that I don’t see get much criticism.

I’ve been reading “The Rise and Fall of Nations” by Ruchir Sharma. What stood out to me was his discussion of immigration where he used a very popular left-of-center talking point that “immigrants do the jobs natives don’t want to do.” He justified this with several anecdotes, but to me this smacks of the same false narrative as “people don’t want to work”. It’s not that natives don’t want to do those jobs, it’s that those jobs are unwilling to pay a higher cost for labor and so usually receive special carve outs and exceptions allowing them to pay less. This in turn makes the jobs unattractive to natives who have other options, and when the job creators whine to the government saying “no one wants to work!” the government responds with selected programs to allow the importation of cheaper workers.

Just look at agriculture in America. In Massachusetts the minimum wage is $14.25, but it’s just $8.00 for farm workers! Farm workers are also except from overtime pay and some OSHA requirements alongside the NLRA and many state laws. The law has excepted farm workers from a majority of the protections and benefits afforded to other workers, so why would anyone work on a farm? Why work on a Massachusetts farm for $8.00 an hour with no overtime, no safety, and no protection when you could make $14.25 an hour working for Walmart. So instead these jobs go to immigrants, especially immigrants on special visas which only allow them to work on farms! There’s no fear of your workers leaving for a better job if your government forbids them from doing so! So let’s be honest, are these jobs that natives don’t want to do? Or are they jobs that natives refuse to do because they have low pay, low benefits, low safety, and there are plenty of better options available.

Farm employers say that it has to be this way: they can’t raise wages or they’d go out of business, or prices would rise, or America’s food economy would be destroyed by cheap imports. This is the same excuse the “no one wants to work” crowd gives for refusing to raise wages, and is strikes me as the same 19th century nonsense that people used to use to argue against the minimum wage and every single worker’s rights law for generations. Which is why it’s so infuriating that many left-of-center voices believe in the “jobs natives don’t want to do” narrative, even while they rightly point out that “no one wants to work” is a false narrative. If farm jobs were as good as Walmart jobs we’d see far more Americans take them.

-

Why is deflation bad?

This topic is probably well known to people with an understanding of economics, but that isn’t most people so I decided I wanted to write about it. With most of the Western world experiencing sky-high inflation these days, people are wondering when prices will ever come down. A reduction in prices would be an example of deflation, and the Fed has for years been working tirelessly against that, which might make some people wonder “why wouldn’t it be a good thing if prices went down?”

To begin with, technology is supposed to be deflationary and in this case it’s seen as a good thing as it allows the economy to grow faster and people to afford more things. However while deflation is expected in certain sectors, the economy as a whole should not be deflationary as it can pervert the market forces which lead to growth. In a deflationary environment, money gains value as time goes on and this means the rich get richer just by holding money, they don’t even have to invest it. Not only that but loans are very expensive because the value of money keeps going up. Both of these facts discourage investment and encourage sitting on wealth instead, which decreases economic growth and productivity.

This is often cited as to why despite its use throughout human history, a gold standard is not appropriate for a modern economy. A gold standard would ensure that money can only be created through mining more gold, and since the economy is expected to continue growing as more people join the workforce and more technology is rolled out, this would by necessity induce deflation. Deflation would then discourage investment and encourage hording, hindering economic growth and ossifying social mobility as old money becomes unassailable by new money.

For all these reasons most central banks have an inflation target of around 2%, let’s all hope they manage to get inflation in line.

-

Will inflation become persistent?

Currently most of the western world is experiencing inflation of between 8% and 15% a year (although there are some stark outliers). The question on everyone’s mind is “will this become persistent,” my question is “how will we know if it has?”

The Federal Reserve’s view that inflation would be “transitory” didn’t seem so unreasonable when they made it in early 2021. Inflation was caused in part by the sudden drop in supply due to the COVID19 pandemic. That drop in supply had also caused a drop in demand, but as the economy opened up demand was rising and it was assumed supply would as well. This could have meant that within a year or two supply and demand would restablize to somewhere around their 2019 levels, when the factories and supply chains were fully staffed and the consumers were fully consuming. But something went wrong, at some point it seems that demand got well ahead of supply and at that point supply couldn’t catch up as long as low rates and easy money remained a policy of the Fed. And so in 2022 the Fed quietly retired the “transitory” label and started raising rates in earnest.

To digress a little, Argentina experienced an inflation rate of around 300% on average from 1975 to 1990, and the results on consumer habits were amazing. People generally spent all their money as soon as they had it, no saving in sight, because inflation erodes the value of saved money almost immediately. People would buy cars as soon as they hit the market, drive the car for a few years, and then sell it used and were able to make a profit because with 300% inflation the price of their car had gone up tremendously even as they drove it. The lack of any sort of savings, and the sky-high demand as people spent every peso they had, both became entrenched in the buying habits of Argentine consumers and those habits were difficult for the central bank to overcome. Worse still, these habits created a “tragedy of the commons” among the Argentine consumers, if everyone would be willing to spend less pesos and save more, then demand could cool off and supply could increase to match it, taming the inflation. But if only some of the consumers stopped spending and started saving, then inflation would persist at sky high levels and all those consumers would accomplish is the swift erosion of whatever money they put towards savings. If you wanted to keep your wealth during hyperinflation, you had to spend it (or convert it to dollars, which also didn’t help the peso).

The persistence of Argentine inflation was what made it so impossible to cool, not just the constant sticker shock. That’s part of why the Federal Reserve has been so deliberate and communicative, it wants to maintain the trust of the American consumers and producers. As long as people trust that the central bank will cool inflation, they will continue to save and not just spend spend spend. But if people don’t trust the institutions (as they did not in Argentina), then any attempts to maintain trust in the currency are futile. I haven’t detected the sort of tell-tale signs that inflation is becoming ingrained in American’s buying habits, we’d know if it had when people start buying things today on the assumption the price will rise in the near future, and I haven’t seen a lot of that. On the other hand I’m a scientist who doesn’t have much money for big purchases, so what do I know about spending habits?

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.