I’m not exactly happy about the recent NIH news. For reference the NIH has decided to change how it pays for the indirect costs of research. When the NIH gives a 1 million dollar grant, the University which receives the grant is allowed to demand a number of “indirect costs” to support the research.

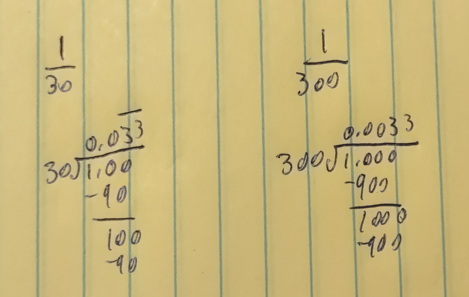

These add up to a certain percentage tacked onto the price of the grant. For a Harvard grant, this was about 65%, for a smaller college it could be 40%. What it meant was that a 1 million grant to Harvard was actually 1.65 million, while a smaller college got 1.4 million, 1 million was always for the research, but 0.65 or 0.4 was for the “indirect costs” that made the research possible.

The NIH has just slashed those costs to the bone, saying it will pay no more than 15% in indirect costs. A 1 million dollar grant will now give no more than 1.15 million.

There’s a lot going on here so let me try to take it step by step. First, some indirect costs are absolutely necessary. The “direct costs” of a grant *may not* pay for certain things like building maintenance, legal aid (to comply with research regulations), and certain research services. Those services are still needed to run the research though, and have to be paid for somehow, thus indirect costs were the way to pay them.

Also some research costs are hard to itemize. Exactly how much should each lab pay for the HVAC that heats and cools their building? Hard to calculate, but the building must be at a livable temperature or no researcher will ever work in it, and any biological experiment will fail as well. Indirect costs were a way to pay for all the building expenses that researchers didn’t want to itemize.

So indirect costs were necessary, but were also abused.

See, unlike what I wrote above, a *university* almost never receives a government grant, a *primary investigator* (called a PI) does instead. The PI gets the direct grant money (the 1 million dollars), but the University gets the indirect costs (the 0.4 to 0.65 million). The PI gets no say over how the University spends the 0.5 million, and many have complained that far from supporting research, the University is using indirect costs to subsidize their own largess, beautifying buildings, building statues, creating ever more useless administrative positions, all without actually using that money how it’s supposed to be used: supporting research.

So it’s clear something had to be done about indirect costs. They were definitely necessary, if there were no indirect costs most researchers would not be able to research as Universities won’t allow you to use their space for free, and direct costs don’t always allow you to rent out lab space. But they were abused in that Universities used them for a whole host of non-research purposes.

There was also what I feel is a moral hazard in indirect costs. More prestigious universities, like Harvard, were able to demand the highest indirect costs, while less prestigious universities were not. Why? It’s not like research costs more just because you have a Harvard name tag. It’s just because Harvard has the power to demand more money, so demand they shall. Of course Harvard would use that extra money they demanded on whatever extravagance they wanted.

The only defense of Harvard’s higher costs is that it’s doing research in a higher cost of living environment. Boston is one of the most expensive cities in America, maybe the world. But Social Security doesn’t pay you more if you live in Boston or in Kalamazoo. Other government programs hand you a set amount of cash and demand you make ends meet with it. So too could Harvard. They could have used their size and prestige to find economies of scale that would give them *less* proportional indirect costs than could a smaller university. But they didn’t, they demanded more.

So indirect costs have been slashed. If this announcement holds (and that’s never certain with this administration, whether they walk it back or are sued to undo it are both equally likely), it will lead to some major changes.

Some universities will demand researcher pay a surcharge for using facilities, and that charge will be paid for by direct costs instead. The end result will be the university still gets money, but we can hope that the money will have a bit more oversight. If a researcher balks at a surcharge, they can always threaten to leave and move their lab.

Researchers as a whole can likely unionize in some states. And researchers, being closer to the university than the government, can more easily demand that this surcharge *actually* support research instead of going to the University’s slush fund.

Or perhaps it will just mean more paperwork for researchers with no benefit.

At the same time some universities might stop offering certain services for research in general, since they can no longer finance that through indirect costs. Again we can hope that direct costs can at least pay for those, so that the services which were useful stay solvent and the services which were useless go away. This could be a net gain. Or perhaps none will stay solvent and this will be a net loss.

And importantly, for now, the NIH budget has not changed. They have a certain amount of money they can spend, and will still spend all of it. If they used to give out grants that were 1.65 million and now give out grants that are 1.15 million, that just means more individual grants, not less money. Or perhaps this is the first step toward slashing the NIH budget. That would be terrible, but no evidence of it yet.

What I want to push back on though, is this idea I’ve seen floating around that this will be the death of research, the end of PhDs, or the end of American tech dominance. Arguments like this are rooted in a fallacy I named in the title: “if the government doesn’t do this, no one will.”

These grants fund PhDs who then work in industry. Some have tried to claim that this change will mean there won’t be bright PhDs to go to industry and work on the future of American tech. But to be honest, this was always privatizing profit and socializing cost. All Americans pay taxes that support these PhDs, but overwelmingly the benefits are gained by the PhD holder and the company they work for, neither of whom had to pay for it.

“Yes but we all benefit from their technology!” We benefit from a lot of things. We benefit from Microsoft’s suite of software and cloud services. We benefit from Amazon’s logistics network. We benefit form Tesla’s EV charging infrastructure. *But should we tax every citizen to directly subsidize Microsoft, Amazon, and Tesla?* Most would say. no. The marginal benefits to society are not worth the direct costs to the taxpayer. So why subsidize the companies hiring PhDs?

Because people will still do things even if the government doesn’t pay them. Tesla built a nation-wide network of EV chargers, while the American government couldn’t even build 10 of them. Even federal money was not necessary for Tesla to build EV chargers, they built them of their own free will. And before you falsely claim how much Tesla is government subsidized, an EV tax credit benefits the *EV buyer* not the EV seller. And besides, if EV tax credits are such a boon to Tesla, then why not own the fascists by having the Feds and California cut them completely? Take the EV tax credits to 0, that will really show Tesla. But of course no one will because we all really know who the tax credits support, they support the buyers and we want to keep them to make sure people switch from ICE cars to EVs

Diatribe aside, Tesla, Amazon, and Microsoft have all built critical American infrastructure without a dime of government investment. If PhDs are so necessary (and they probably are), then I don’t doubt the market will rise to meet the need. I suspect more companies will be willing to sponsor PhDs and University research. I suspect more professors will become knowledgeable about IP and will attempt to take their research into the market. I suspect more companies will offer scholarships where after achieving a PhD, you promise to work for the company on X project for Y amount of years. Companies won’t just shrug and go out of business if they can’t find workers, they will in fact work to make them.

I do suspect there will be *less* money for PhDs in this case however. As I said before, the PhD pipeline in America has been to privatize profits and subsidize costs. All American taxpayers pay billions towards the Universities and Researchers that produce PhD candidates, but only the candidates and the companies they work for really see the gain. But perhaps this can realign the PhD pipeline with what the market wants and needs. Less PhDs of dubious quality and job prospect, more with necessary and marketable skills.

I just want to push back on the idea that the end of government money is a deathknell for industry. If an industry is profitable, and if it sees an avenue for growth, it will reinvest profits in pursuit of growth. If the government subsidizes the training needed for that industry to grow, then instead it will invest in infrastructure, marketing, IP and everything else. If training is no longer subsidized, then industry will subsidize it themselves. If PhDs are really needed for American tech dominance, then I absolutely assure you that even the complete end of the NIH will not end the PhD pipeline, it will simply shift it towards company-sponsored or (for the rich) self-sponsored research.

Besides, the funding for research provided by the NIH is still absolutely *dwarfed* by what a *single* pharma company can spend, and there are hundreds of pharma companies *and many many other types of health companies* out there doing research. The end of government-funded research is *not* the end of research.

Now just to end on this note: I want to be clear that I do not support the end of the NIH. I want the NIH to continue, I’d be happier if its budget increased. I think indirect costs were a problem but I think this slash-down-to-15% was a mistake. But I think too many people are locked into a “government-only” mindset and cannot see what’s really out there.

If the worst comes to pass, and if you cannot find NIH funding, go to the private sector, go to the non-profits. They already provided less than the NIH in indirect costs but they still funded a lot of research, and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Open your mind, expand your horizons, try to find out how you can get non-governmental funding, because if the worst happens that may be your only option.

But don’t lie and whine that if the government doesn’t do something, then nobody will. That wasn’t true with EV chargers, it isn’t true with biomedical research, and it is a lesson we all must learn if the worst does start to happen.