Revealed preference is a very important economic concept because quite simply: talk is cheap. You cannot poll people on what they economically most want, because humans are want to lie about ourselves so that we appear more noble, more virtuous, and so on. You cannot poll people, instead you have to look at what people *do*.

To explain revealed preference in simple terms: actions speak louder than words. People like to claim that they eat healthily, that they care about what they’re putting into their bodies. But many of those very same people fill their shopping cart with junk food at the expense of all else. So while they claim to eat healthily, they are revealed to eat junk food. Their revealed preference is that they prefer the taste of junk food over the benefits of healthy food, but you wouldn’t know it by talking to them.

At a societal level, revealed preference also shows up whenever popular causes force people to put their money where their mouth is. Reducing plastic waste polls really well, and large segments of society claim that they would happily pay more for a biodegradable option rather than pay less for a plastic option. But the data from supermarkets doesn’t bear this out, with nearly all consumers continuing to prefer a cheaper plastic option when available compared to a more expensive biodegradable option.

So when economists try to understand what drives people’s economic activity, whether it’s what they buy, where they work, or how they commute, one cannot rely on what people *say* they do, you must instead find out what they *actually* do. Because the gap between words and actions is massive and we all want to appear more noble than we truly are.

With revealed preference comes the tantalizing, but tricky prospect of studying *revealed belief*. Revealed *preference* is just showing what *actions* people take that are contrary to their statements. But revealed *belief* would be about showing *the reasoning behind those actions*.

To give an example, lets dissect the junk food vs healthy food choice. You might find people who adamantly claim that they eat healthy food *not just* for their health. They may claim that healthy food tastes better, is more convenient, and is even cheaper than junk food. But if that same person is revealed to mostly eat junk food, we can surmise that their stated beliefs about healthy food vs junk food (that it tastes better, is more convenient, and even cheaper) are also wrong.

Such a person who claims to eat healthy food but only eats junk food clearly has significant cognitive dissonance, or is just *lying* in order to seem healthier. It isn’t just that their actions belie their beliefs, rather their *revealed beliefs* are contradictory to their *stated beliefs*. They probably don’t actually believe healthy food is tastier and cheaper, they just say that to try to further the lie that they eat only healthy food. Their real belief is that junk food is tastier and cheaper, that’s why they buy it and eat it.

This *revealed beliefs* thing is tricky though because there could be several confounding factors. Say someone *only states* that they believe healthy food is tastier than junk food. If they are then revealed later to be buying junk food, is it because they actually don’t think healthy food is tastier? Or is it because the cheapness of junk food and the expensiveness of healthy food outweighs taste considerations? There can always be some other reason that people take their actions, outside of their stated reasons.

But with recent events, I do think I’ve seen a mass example of revealed beliefs. And it’s with tariffs.

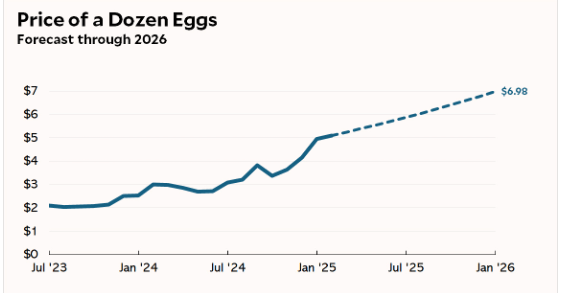

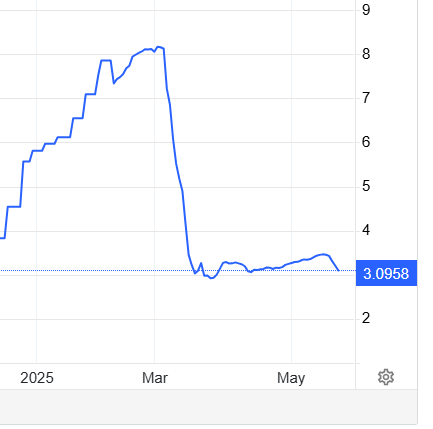

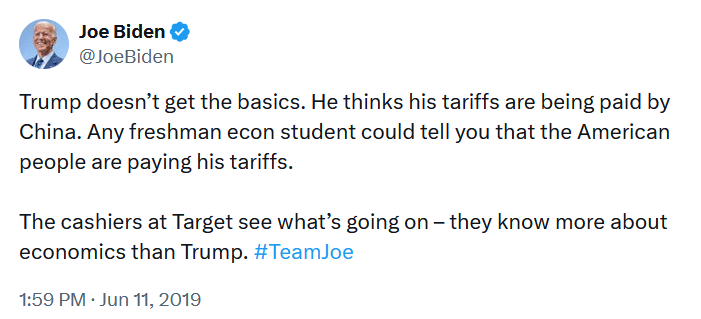

When Trump was coming on the scene, first in 2016 and again in 2024, economists and political commentators from both sides of the Atlantic argued passionately against his tariffs on every conceivable level. Trump’s tariffs weren’t just a good idea taken too far, rather *any tariffs at all* would harm consumers and depress the American economy to unimaginable levels. Even tariffs against geopolitical foes like China should be avoided, as such tariffs harmed America a lot more than they harmed China, and so ultimately would be counterproductive.

Yet today in 2026 I see *many of those exact same people*, primarily from the European and Canadian parts of the Atlantic, argue passionately that the EU and other nations *must respond in kind* to Trump’s tariffs. That Europe and Canada should raise massive counter-tariffs against Trump, equal or greater in value to whatever he is levying against them, and specifically targeted at America’s major industries. When Trump’s team met EU officials and agreed to a “deal” whereby the US would raise tariffs and the EU would not respond in kind, this was seen as a disaster, a surrender, and a damning indictment.

It seems clear that there is a revealed belief going on here. These transatlantic thinkers claim that tariffs hurt America more than they hurt the tariffed countries, but if that were the case, then counter-tariffs would hurt the EU and Canada more than they’d hurt America. The “solution” to Trump’s trade war would then be to do nothing at all. LET Trump tariff every nation to high heaven, he’s primarily hurting America after all, and don’t respond in kind under any circumstances. Don’t tariff American products, don’t go after American businesses, don’t do anything differently than you’d normally do, because any such anti-trade measure would harm your own countries more than it harms America.

But the revealed belief here is that Trump’s tariffs *do* harm other countries more than they harm America, because counter-tariffs and other trade barriers are being called upon, on the assumption that they will harm America more than they’ll harm other nations. It seems that many transatlantic thinkers are revealing that all the rhetoric around tariffs was a Noble Lie. All the claims about how tariffs are ineffective and self-destructive were lies meant to dissuade the public from supporting tariffs in the first place. But now that the tariffs are out of the bag, the Noble Lie has no more use, and the Awful Truth about tariffs, that they are harmful to one’s own nation, but are effective at countering trade imbalances, has come to the fore.

Noble Lies such as this beclown the person saying the lie. They reveal the liar to be a hypocrite and untrustworthy. If you found that the person who goes on and on about healthy food was actually eating nothing but junk food, you’d probably never again trust their recommendations to you about healthy eating. And likewise, a lot of poli/econ commentators have lost a lot of credibility in my eyes by going back on their pre-Trump claims about tariffs. By revealing that they never believed those things in the first place, they reveal (to me at least) that I should never trust them again going forward.