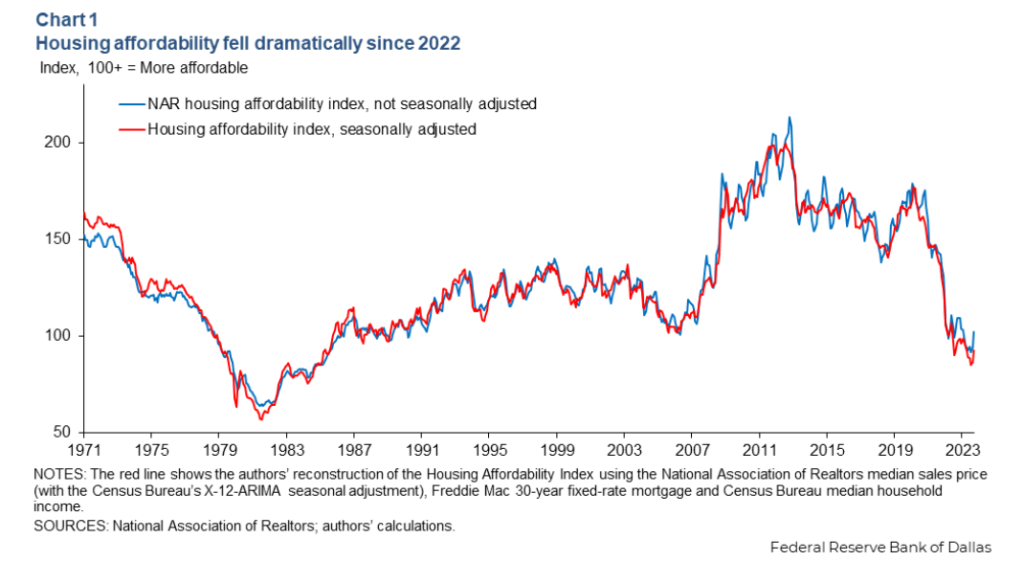

And the US is getting the inflation it clearly wants.

Contrary to the title, this post will only be about America, because I don’t have any real insight into the CCP that hasn’t been covered elsewhere. But I read this article running cover for Biden’s disastrous policy of protectionism, and wanted to post my thoughts.

The central premise of the article is that cutting off trade with China is good because they’re a fascist and expansionist foreign adversary. Now, that’s also a great reason to cut off trade with Saudi Arabia, but America’s trade policy isn’t actually about foreign policy, as you’ll soon find out.

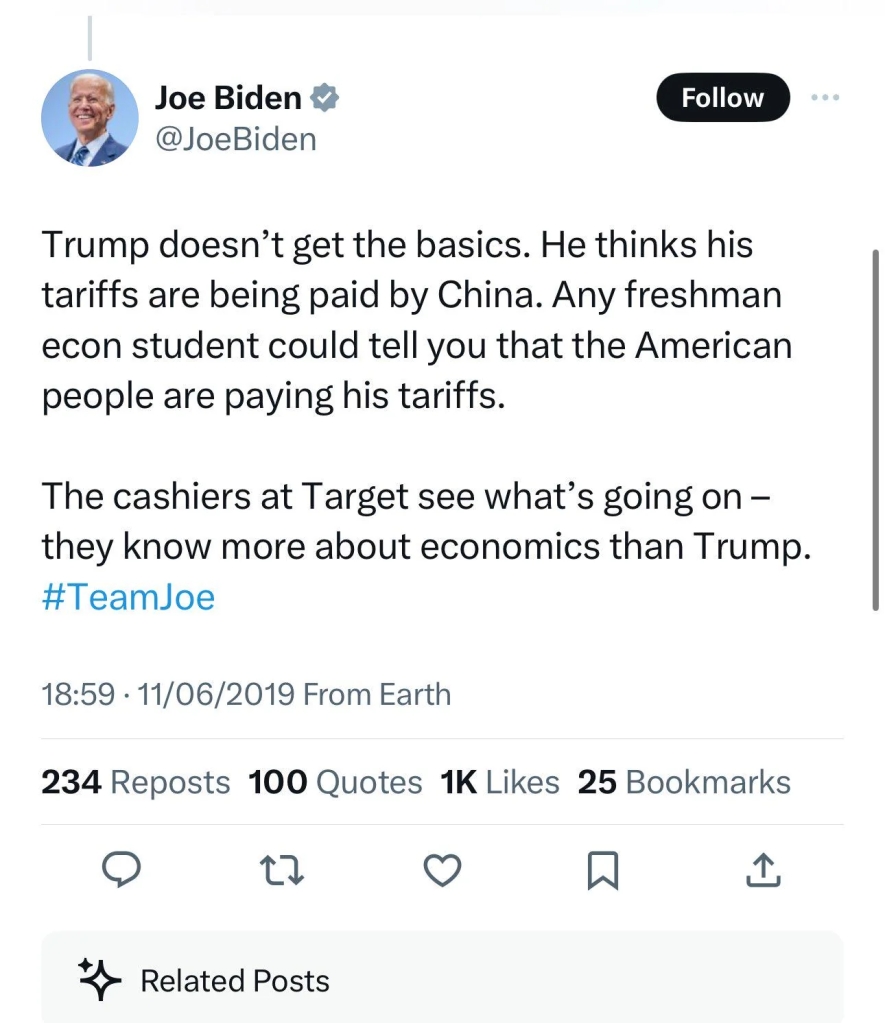

Even more importantly, tariffs don’t hurt the country you’re tariffing, or at least they hurt them *less* than they hurt your *own country*. Even Biden knows that, just ask the Biden of 2019

Tariffs are a great way to push up your own country’s inflation by taxing supply without reducing demand. Furthermore, even if you don’t buy Chinese products you will be paying for this inflation because of substitution effects: someone who is no longer able to buy a Chinese EV may instead purchase an American car, increasing demand for American cars and therefore driving up their price.

There’s two great ways to understand how terrible tariffs are. First, think of the oil shock in the 1970s: middle east nations cut off America’s access to oil and gas from their countries, causing spiraling prices and runaway inflation. By blocking America’s access to energy, they were able to put an economic squeeze that defined the decade.

China is being tariffed on solar power, wind power, and green industries of all kinds, and China makes up more of our imports than the middle east ever did. Spiraling prices are yet again on the menu.

Furthermore, think of Britain’s strategy against Germany during both World Wars. Britain used its powerful navy to prevent Germany from importing goods. This caused shortages and spiraling inflation, leading to riots that overthrew the government in the First World War and overwhelming shortages during the Second.

Tariffs are a way for us to do to ourselves what our enemies would do to us in war: restrict the import of needed goods.

Finally, consider Biden’s empty words about the “existential threat” posed by Climate Change. If Climate Change is dire, then why is Biden raising tariffs on solar power, wind power, and EVs, rather than Chinese oil and Chinese airplanes? Biden is essentially setting up an “anti-carbon tax,” in which polluting industries are exempt from a tax being paid by green industries.

The truth is that none of this is about national security, anymore than the Japan Scare of the 1980s was about national security. Just look at how Japan’s peaceful economic expansion was seen back then:

“The Danger from Japan.” Mr. White warned that the Japanese were seeking to create another “East Asia Co‐prosperity Sphere”-this time by their “martial” trade policies, and that they would do well to “remember the course that ran from Pearl Harbor to the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

Biden is a 1980s style politician, with the (failed) economic outlook of that time. When he sees foreigners being successful it makes him scared, so he raises tariffs to “protect” American industries. But far from protecting industries, tariffs only harm them.

Industries rely on consumers to sustain them, but tariffs are a tax on consumers, sucking up consumer surplus and leaving less money for consumers to spend on domestic industries. Politicians think that domestic industries can magically appear to replace all the foreign ones, but simply put: no man is an island and nor is any country. Autarky is the failed economic policy of fascism, not an economic model for democracies.

Just look at a country like Brazil. Heavy tariffs were supposed to promote domestic industries and help consumers. Instead, consumers pay exorbitant prices for things like video games, while Brazil’s gaming industry remains anemic relative to the nation’s size and wealth. Brazilian cars, Brazilian microchips, and Brazilian steel are not the envy of the world.

And it isn’t because Brazilians are bad at industry, its because their government is doing everything it can to stop them. The high tariffs on everything from steel to cars to microchips are supposed to spur domestic industry, but who’s going to open up a factory when you have to pay those high tariffs just to import the machines and inputs needed to make your products?

Biden is a protectionist because he’s a protectionist. Not because China or Canada are scary or because he needs to fight climate change. But to be fair, Trump is just as protectionist as Biden if not more-so. It’s clear that the current crop of American politicians supports higher inflation and poorer consumers. And that bodes ill if you want to see America succeed and its enemies fail.